Why seven out of ten Caribbean infrastructure projects face delays: how Implementation Science offers a systematic solution

The Pattern We Keep Repeating

A road rehabilitation project in Jamaica takes three years longer than planned. A water infrastructure initiative in Saint Lucia stalls during procurement. A climate resilience project in Dominica struggles with scope changes and budget revisions. Different islands, different sectors, same story: Caribbean development projects consistently take far longer to deliver than originally planned.

The Caribbean Development Bank confronted this reality directly at their June 2025 Annual Meeting in Brasília. Their baseline assessment of 35 projects across ten Caribbean countries revealed what practitioners already knew from experience: persistent procurement delays, institutional capacity constraints, procedural inefficiencies, and oversight issues hamper project implementation across the region. But the assessment went further, identifying fragmented stakeholder coordination, disjointed communication, limited engagement during implementation, and insufficient on-the-ground readiness as factors negatively affecting project outcomes.

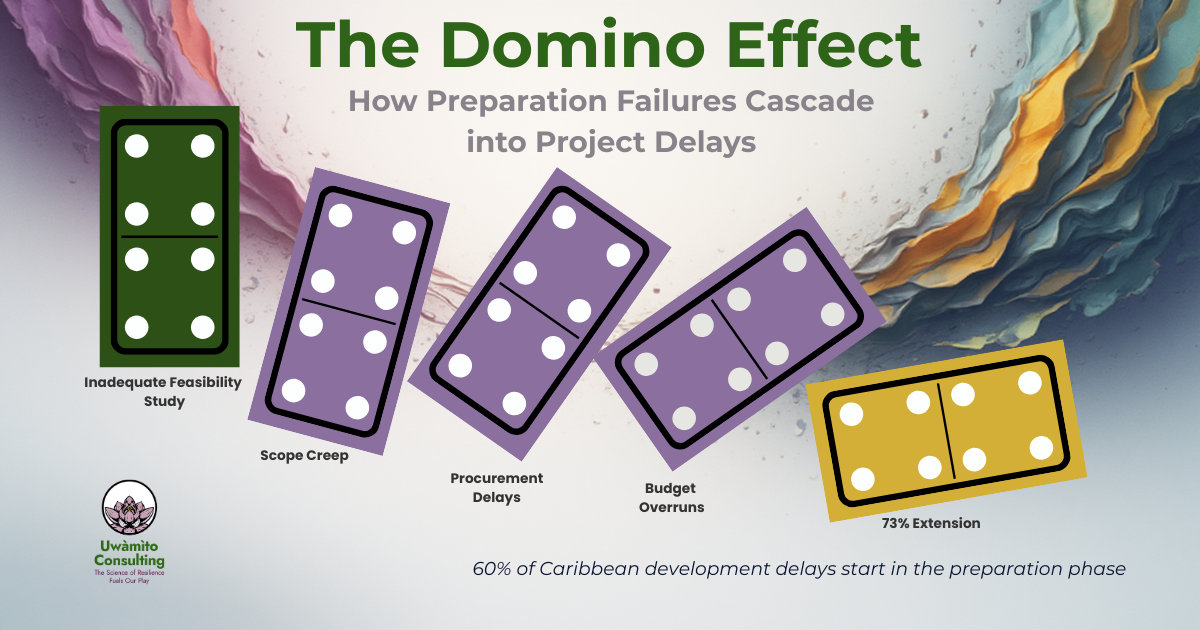

This is not a Caribbean-specific problem. A global analysis by the CoST Infrastructure Transparency Initiative examined 480 projects across three continents and found that 70% faced delays, with projects taking on average 73% longer than originally planned. The critical finding: 60% of delay drivers could be traced back to shortcomings in the preparation phase rather than issues arising during tendering or contract execution.

When delays are downstream symptoms of upstream planning failures, fixing procurement processes or improving construction management will not solve the fundamental problem. The solution requires looking upstream to where projects are designed, scoped, and prepared.

Why Implementation Science Matters

Implementation Science provides systematic frameworks for understanding why interventions succeed or fail when translated from design into practice. The discipline distinguishes between the intervention itself (the infrastructure project, the policy reform, the capacity building programme) and implementation strategies (the methods used to enhance adoption, integration, and sustainability of that intervention).

For Caribbean development projects, this distinction proves essential. Most project delays do not stem from poor technical design. Engineers know how to design roads, water systems, and climate resilience infrastructure. The failures occur in the implementation process: how projects move from concept through feasibility assessment, stakeholder engagement, resource mobilisation, execution, and sustainment.

The EPIS Framework (Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment) offers a particularly useful lens for understanding project delays. EPIS frames implementation as four sequential phases, each with distinct tasks and common failure points:

Exploration Phase: Organisations recognise a need, seek interventions that fit their context, and make decisions about adoption. In Caribbean development projects, this phase often gets compressed. Donors identify needs, governments respond to funding windows, and projects get designed to match available financing rather than genuine implementation readiness.

Preparation Phase: Teams plan, secure resources, train staff, and restructure systems to support implementation. The CoST analysis found this is where 60% of delays originate. Poor feasibility studies, unclear scope, and inadequate financial planning set off a domino effect that carries through to execution. In Caribbean contexts, preparation failures often reflect capacity constraints. Small technical teams managing multiple priority projects simultaneously, limited access to specialised expertise for complex assessments, and pressure to move quickly to secure time-bound funding.

Implementation Phase: Organisations execute, learn, and adapt in real time. Even well-prepared projects encounter unexpected challenges. The difference lies in whether systems exist to detect problems early and adapt effectively. The CDB assessment highlighted disjointed communication and limited engagement as implementation barriers. Organisations struggle to maintain coordination across government ministries, contractors, consultants, and communities when projects encounter inevitable challenges.

Sustainment Phase: Organisations monitor, improve, and institutionalise practices to ensure long-term effectiveness. For infrastructure projects, this means ongoing maintenance, institutional knowledge retention, and adaptive management as contexts evolve. Caribbean projects often lack clear sustainment planning from the outset, treating completion of construction as the endpoint rather than recognising that infrastructure requires decades of active management.

The Preparation Phase Gap: What the Evidence Shows

The CoST research identified three primary preparation failures that cascade into delays:

Poor feasibility studies that fail to adequately assess technical, financial, environmental, or social dimensions. In Caribbean SIDS contexts, feasibility studies often apply templates designed for larger economies without adjusting for limited domestic contractor capacity, small markets for specialised materials, or vulnerability to external shocks from hurricanes and supply chain disruptions.

Unclear scope that leaves critical project elements undefined or subject to later negotiation. Scope ambiguity particularly affects projects requiring cross-ministry coordination or community engagement, common in climate adaptation and social infrastructure projects where technical interventions intersect with complex governance and social systems.

Inadequate financial planning that underestimates true costs or fails to secure realistic financing pathways. Caribbean governments often face constraints in counterpart funding, creating mismatches between donor expectations and government capacity. Projects get designed based on optimistic cost estimates without adequate contingency planning for currency fluctuations, import delays, or disaster recovery needs.

The CDB study added institutional and organisational factors specific to Caribbean implementation contexts:

Institutional capacity constraints where public sector entities lack sufficient staff with relevant technical competence, appropriate training, adequate numerical capacity, necessary digital infrastructure, or financial support to manage complex projects effectively. As one expert noted at the CDB seminar, "You can have someone brilliant at project execution, but if they're one of two people managing a $50 million project, it won't work."

Procurement delays that extend timelines and erode stakeholder confidence. Small island markets mean limited competition for major contracts, while international procurement processes designed for transparency can become bureaucratically burdensome without proportionate benefit in thin markets.

Oversight gaps where monitoring systems fail to detect problems early or lack authority to mandate corrective action. Fragmented accountability across funding agencies, implementing ministries, and executing contractors creates confusion about who holds responsibility for addressing emerging issues.

Applying Implementation Science Frameworks to Caribbean Projects

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) provides a systematic approach to diagnosing where projects go wrong and designing targeted solutions. CFIR organises factors associated with effective implementation across five domains:

1. Intervention Characteristics: The Project Itself

CFIR asks: What are the core components? What evidence supports it? How complex is it? How adaptable? What are the costs?

For Caribbean infrastructure projects, complexity often exceeds local implementation capacity. A climate-resilient water system involves civil engineering, environmental assessment, community engagement, financial management, procurement, and ongoing operations and depending on the specific context there might be other contextual factors involved. Each component requires specialised expertise that may not exist within a single government ministry. Projects succeed when design recognises this complexity and builds in technical assistance, phased approaches, or partnerships that provide missing capabilities.

Adaptability matters particularly in Caribbean contexts where hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, and other shocks can fundamentally alter project conditions mid-implementation. Rigid project designs that cannot accommodate necessary adaptations create delays when inevitably required scope changes trigger lengthy approval processes with donors or financing institutions.

2. Outer Setting: The External Environment

CFIR examines external policies, incentives, beneficiary needs, and inter-organisational networks.

Caribbean development projects operate in a distinct outer setting: small economies heavily dependent on tourism and external markets, high public debt limiting fiscal space, vulnerability to climate shocks, significant brain drain affecting technical capacity, and complex regional coordination through CARICOM and sub-regional mechanisms. Successful projects account for these realities rather than assuming conditions that exist in larger, more stable economies.

The policy environment particularly affects climate finance and regional infrastructure. Projects that navigate multiple national regulatory frameworks (for transboundary water resources or regional energy interconnection) or align with rapidly evolving global climate financing mechanisms require sophisticated understanding of the outer setting. Preparation failures often stem from inadequate assessment of these external factors.

3. Inner Setting: The Implementing Organisation

CFIR assesses organisational culture, implementation climate, and readiness for change.

The CDB study emphasised the need for "a result-driven culture" rather than cultures focused solely on planning or compliance. Caribbean public sector organisations often face conflicting pressures: demands for transparency and accountability that slow decision-making, political cycles that create uncertainty about project continuity, and limited authority to offer competitive compensation that drives talent retention challenges.

Implementation climate includes the tangible resources available (adequate staffing, appropriate technology, sufficient budget) and the intangible aspects (leadership support, clear priorities, tolerance for learning from failure). Projects that proceed without assessing implementation readiness (whether the implementing organisation actually has the climate to support successful execution), predictably encounter delays when these gaps manifest during implementation.

4. Characteristics of Individuals: The People Involved

CFIR considers the knowledge, beliefs, and self-efficacy of implementers.

Small Caribbean states face particular challenges with individual capacity. Technical expertise concentrates in limited numbers of professionals who simultaneously manage multiple priority initiatives. One person might lead disaster risk reduction while also serving on climate finance proposal teams and managing bilateral donor relationships. When key individuals leave for opportunities abroad or move to private sector roles, institutional knowledge departs with them.

Projects that depend entirely on external consultants for technical functions create vulnerabilities when those consultants depart. Successful approaches invest in capacity building for local teams, pair international expertise with national counterparts for knowledge transfer, and document systems clearly enough that transitions do not stall progress.

5. Implementation Process: How Execution Unfolds

CFIR examines planning, engaging stakeholders, executing interventions, and reflecting on progress.

The CDB assessment found that fragmented stakeholder coordination and disjointed communication hamper Caribbean projects. Infrastructure projects typically involve multiple ministries (finance, planning, line ministries, environment), statutory authorities, contractors, consultants, affected communities, and financing partners. Without clear processes for coordination, decision-making becomes paralysed by unclear authority or conflicts between stakeholders.

Reflection mechanisms (structured processes for monitoring progress, detecting problems early, and adjusting course) often get neglected under pressure to execute. Yet these processes distinguish projects that adapt successfully from those that continue implementing poorly designed approaches until failures become catastrophic.

Practical Solutions: Implementing Implementation Science

Caribbean governments, development finance institutions, and implementing organisations can apply Implementation Science principles to reduce project delays through targeted interventions at each EPIS phase:

Exploration: Improve Project Selection

Strategy: Assess implementation readiness before commitment

Use rapid assessment tools that evaluate whether the implementing organisation possesses the necessary capacity (technical skills, adequate staffing, appropriate systems), whether the political and policy environment supports the intervention, whether financing aligns with realistic cost projections, and whether key stakeholders demonstrate genuine commitment rather than compliance-driven approval.

Uwamito Consulting's Project Triage Diagnostic tool provides systematic assessment of these readiness factors, identifying gaps that require remediation before proceeding. This upstream investment prevents downstream delays far more effectively than attempting to fix capacity gaps during active implementation.

Strategy: Match project complexity to implementation capacity

Not every infrastructure need requires a $50 million intervention. In contexts with limited implementation capacity, smaller phased approaches may deliver better outcomes than attempting comprehensive transformation. Implementation Science evidence suggests starting with minimum viable interventions that demonstrate success, build capacity and confidence, and create foundations for subsequent phases.

Preparation: Strengthen Project Design

Strategy: Invest proportionately in preparation

The CoST evidence suggests that inadequate preparation accounts for 60% of delay drivers. Yet preparation phases often get compressed under pressure to commit funds within donor timelines or political cycles. A systematic principle emerges: preparation investment should scale with project complexity, risk, and cost. A $50 million climate infrastructure project justifies six to twelve months of thorough feasibility assessment, stakeholder engagement, capacity assessment, and detailed planning. Attempting to prepare such projects in 30-60 days creates the conditions for subsequent delays.

Strategy: Conduct Caribbean-contextualised feasibility assessments

Standard feasibility templates often overlook factors critical to Caribbean implementation: limited contractor markets requiring phased procurement to maintain competition, import dependencies requiring contingency planning for supply chain disruptions, hurricane seasons that define practical construction windows, institutional capacity for operations and maintenance beyond construction, and social dynamics in small communities where infrastructure projects create disproportionate local impacts.

Strategy: Build in adaptive management from design

Projects designed with rigid specifications and change-averse contracts create delays when inevitable adaptations become necessary. Incorporate structured flexibility: phased designs that allow course correction between phases, pre-approved adaptation protocols for defined scenario categories, contingency budgets for justified scope adjustments, and clear decision-making authority for field-level adaptations within defined parameters.

Implementation: Improve Execution Systems

Strategy: Establish coordination mechanisms

The CDB study identified fragmented stakeholder coordination as a key barrier. Successful projects establish clear coordination structures: a project implementation unit with dedicated staff rather than additional responsibilities for already-stretched ministry teams, defined escalation pathways for resolving issues, regular coordination meetings with decision-making authority, and communication protocols that keep all stakeholders informed without creating information overload.

Strategy: Use adaptive learning systems

Implementation Science emphasises learning during execution. Establish regular reflection points (monthly or quarterly depending on project duration) where teams assess what is working, what is not working, why, and what adjustments would improve outcomes. Document lessons for institutional memory. Create psychological safety for raising problems early rather than concealing difficulties until crises emerge.

Strategy: Deploy appropriate technical assistance

The CDB assessment noted that beneficiary institutions must participate meaningfully in design, particularly for capacity building and technology transfer. Embed technical assistance within implementing teams rather than parallel consultancy structures. Pair international expertise with national counterparts for explicit knowledge transfer. Define clear graduation criteria for reducing external support as local capacity develops.

Sustainment: Plan for Long-term Success

Strategy: Design for maintenance from the outset

Infrastructure requires decades of active management. Projects that treat completion of construction as the endpoint predictably fail when maintenance lapses or operational expertise departs. Include in project preparation: realistic operating cost projections and revenue mechanisms, maintenance protocols with required skills clearly specified, training programmes for operations teams, and institutional arrangements for continued oversight.

Strategy: Build institutional knowledge systems

Small Caribbean states cannot afford to lose critical project knowledge when key individuals depart. Systematically document decisions, rationale, lessons learned, and operational procedures. Create accessible knowledge repositories. Build redundancy in critical skills rather than depending on single individuals.

Strategy: Establish feedback loops

Sustainment succeeds when systems exist to detect deteriorating performance and trigger remedial action. Include provisions for ongoing monitoring, clear performance indicators that signal when intervention is needed, and institutional authority to act on early warning signals.

What Success Looks Like

These approaches may sound burdensome: more assessment, more planning, more systems. The Implementation Science evidence suggests otherwise. Systematic preparation and structured implementation processes accelerate delivery by preventing delays rather than reacting to crises.

Consider what happens when projects follow Implementation Science principles:

A water infrastructure project conducts thorough implementation readiness assessment during exploration and discovers the executing authority lacks adequate procurement expertise. Rather than proceeding and encountering procurement delays during implementation, the project preparation phase includes embedding a procurement specialist who simultaneously manages immediate needs and builds internal capacity. The project executes on schedule, and the authority retains enhanced procurement capability for future initiatives.

A climate adaptation project designs with hurricane season constraints explicitly incorporated. Rather than experiencing construction delays when contractors shut down during hurricane threats, the project timeline accounts for these realities from the outset. Stakeholders maintain confidence because the project meets realistic expectations rather than repeatedly revising overly optimistic schedules.

A road rehabilitation initiative establishes clear coordination protocols during preparation, defining how the implementing ministry, contractor, utility companies, and affected communities will communicate and make decisions. When underground utilities are discovered that require scope changes, the established process allows rapid resolution rather than weeks of unclear responsibility and delayed decisions.

Moving Forward

The 73% problem is not inevitable. Caribbean development projects take far longer than planned because we consistently underinvest in preparation, fail to assess implementation readiness, and proceed without the coordination systems and adaptive capacity that execution requires.

Implementation Science offers tested frameworks and strategies for addressing these challenges systematically. The solutions do not require massive additional investment. They require redirecting effort from reactive crisis management to proactive preparation and structured implementation.

For Caribbean governments: Assess implementation readiness before committing to complex projects. Invest preparation time proportionate to project scale and complexity. Establish coordination mechanisms and adaptive learning systems as standard practice.

For development finance institutions: Adjust approval processes to reward thorough preparation rather than penalising time spent on proper feasibility assessment and stakeholder engagement. Provide technical assistance that builds implementing organisation capacity rather than creating parallel systems. Allow structured flexibility for justified adaptations rather than requiring rigid adherence to initial designs that prove inadequate.

For implementing organisations: Develop internal competencies in Implementation Science frameworks. Use systematic approaches to assess barriers and select appropriate strategies. Build feedback loops and learning systems that improve performance across all projects.

The evidence is clear. The frameworks exist. The question is whether we will continue repeating the pattern of delays, or whether we will apply what Implementation Science teaches about preparing thoroughly, implementing systematically, and adapting thoughtfully.

Uwàmìto Consulting specialises in applying Implementation Science frameworks to strengthen Caribbean development projects. Our Project Triage Diagnostic tool provides rapid assessment of implementation readiness and identifies targeted strategies to prevent delays before they occur. Contact us to discuss how systematic preparation can accelerate your project delivery.

References

Caribbean Development Bank. (2025). Accelerating Project Implementation to Reduce Poverty [Seminar proceedings]. 55th Annual Meeting, June 11, 2025, Brasília, Brazil. https://www.caribank.org/newsroom/news-and-events/seminar-1-accelerating-project-implementation-reduce-poverty

Caribbean News Global. (2025, June 27). CDB study reveals procurement delays, oversight gaps, and weak capacity undermining Caribbean development projects. https://caribbeannewsglobal.com/cdb-study-reveals-procurement-delays-oversight-gaps-and-weak-capacity-undermining-caribbean-development-projects/

CoST Infrastructure Transparency Initiative. (2025, May 20). Drivers of infrastructure delays: What can 480 projects across three continents teach us? [Research report]. https://infrastructuretransparency.org/2025/05/20/drivers-of-infrastructure-delays/

Aarons, G. A., Hurlburt, M., & Horwitz, S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4-23.

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for implementation research. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50.

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65-76.